|

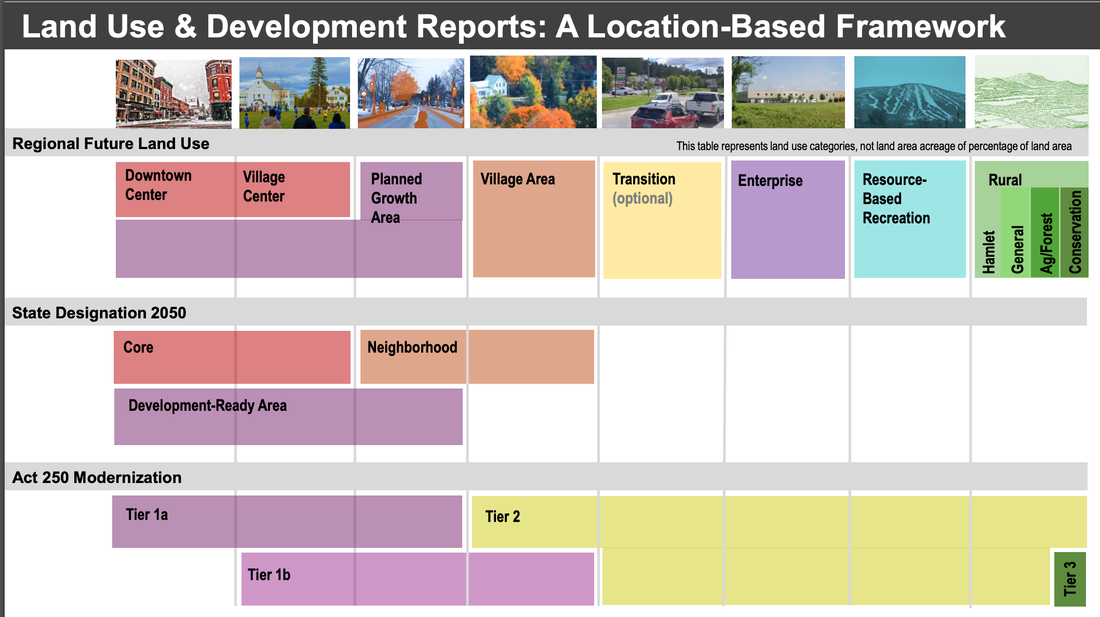

One of the biggest bills we will work on this session is a significant and (I think) very exciting overhaul of Act 250. The Senate Natural Resources and Energy version of this is S.308. But before I get into it, here's a little background. For a primer on Act 250 (Vermont's signature land-use planning law), for the history of its origins, and for an overview of its current problems, I highly recommend VPR's Brave Little State podcast on Act 250. What do I think about Act 250? I'm grateful for the environmental backstop that it provided to Vermont, especially for the towns that didn't and don't have zoning regulations, but I also believe Act 250 no longer serves Vermonters as well as it once did. In the last 50 years, many towns have adopted zoning regulations that duplicate the criteria for Act 250 and it's clear that Act 250 has 1. Prevented good development in our downtowns and village centers, 2. Not prevented sprawl, and 3. Not protected significant ecological sites. Here's the good news: Within the last few months of 2023 there were three studies all having to do with Act 250 (1. Regional Future Land Use, 2. State Designation 2050, and 3. Natural Resource Board's Necessary Changes to Act 250 aka "Act 250 Modernization"), which astonishingly, across a broad spectrum of stakeholders, had a high degree of alignment of their suggestions for how to modernize Act 250. Recommended by both environmental advocates and housing advocates, this set of consensus suggestions represents the package of changes that are currently represented in S.308. In testimony on this, it was delightfully refreshing to hear economic development champions to call for better regulation to prevent forest fragmentation and defending Vermont's pristine ecological sites, and then to hear from environmental advocates on the need for more housing in our already-developed downtowns. I hope this description conveys how magical and significant this consensus is. The current paradigm of Act 250 is "threshold based". If you build too much or too fast, it triggers regulation. The new paradigm embodied in all three of these reports is a shift to "location based" regulation. There are some places where we want to encourage development, like in our downtowns and village centers, which are already well-regulated. And there are some places that are so ecologically sensitive or significant that ANY development should be regulated there, even if it's just one unit of housing. The language that we have been using in committee to distinguish between different types of places comes from the "Necessary Changes to Act 250" report (aka the NRB report), which uses a tier system. Tier 1a: These are downtowns or previously-developed areas, with access to water and sewer, in cities and towns which have such robust zoning that Act 250 is duplicative. These are places that will likely either be exempt from Act 250, or they may locally administer the Act 250 process, or something similar. Tier 1b: Village centers or towns which may not have access to both water and sewer, and who's zoning may not be quite as robust as checking all of the boxes of Act 250, but maybe they check some of the boxes. And so these areas would get some level of either exemption or self-administration of Act 250 that corresponds to the zoning the do have or some other loosening of the regulations. Tier 2: Rural areas that are not Tier 3. Act 250 would continue to apply here potentially with an additional provision called the "road rule" that would help prevent forest fragmentation, like the kind seen in Charlie Hancock's testimony from Montgomery, VT (his part starts at 29:40). Tier 3: I'll quote the bill as it currently stands: "These lands have significant ecological value, and require special protection due to their uniqueness, fragility, or ecological importance. They may include protected lands, areas with specific features like steep slopes or endangered species, wetlands, flood hazard areas, and shoreline protection areas and are intended to remain largely undeveloped for the benefit of future generations."

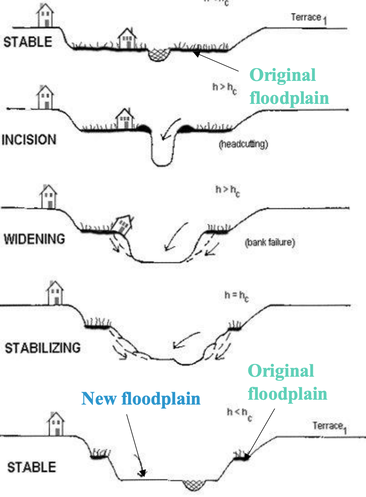

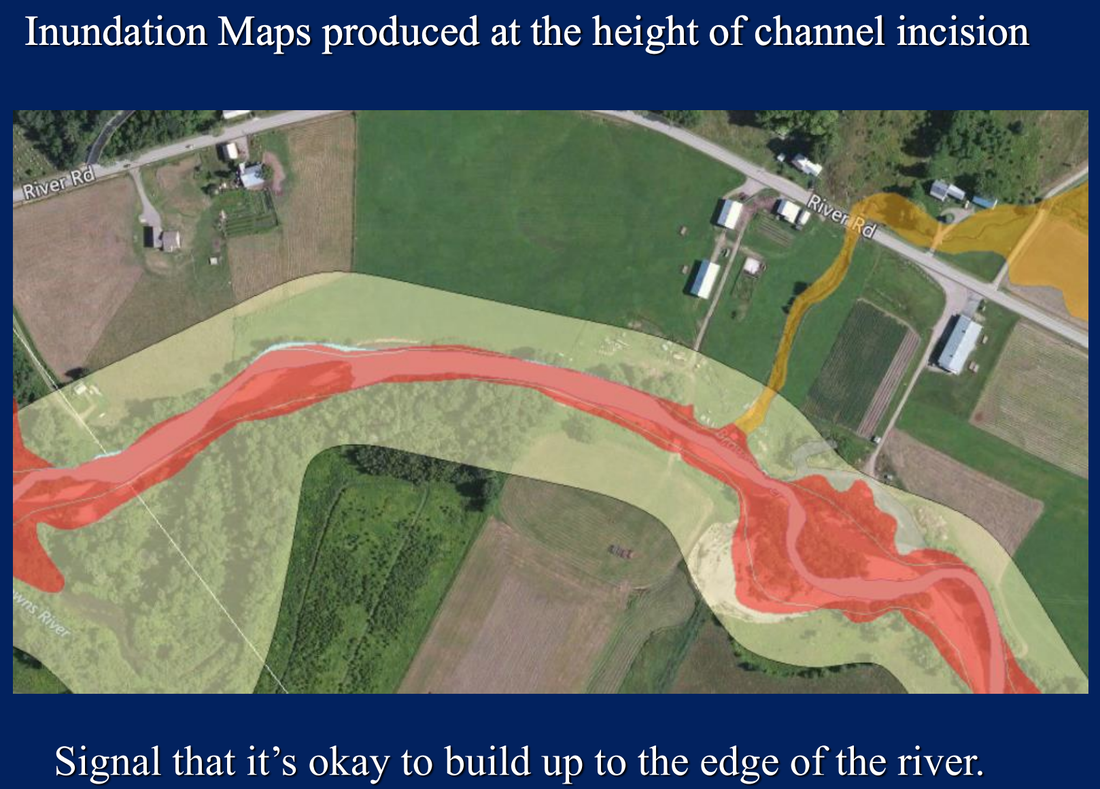

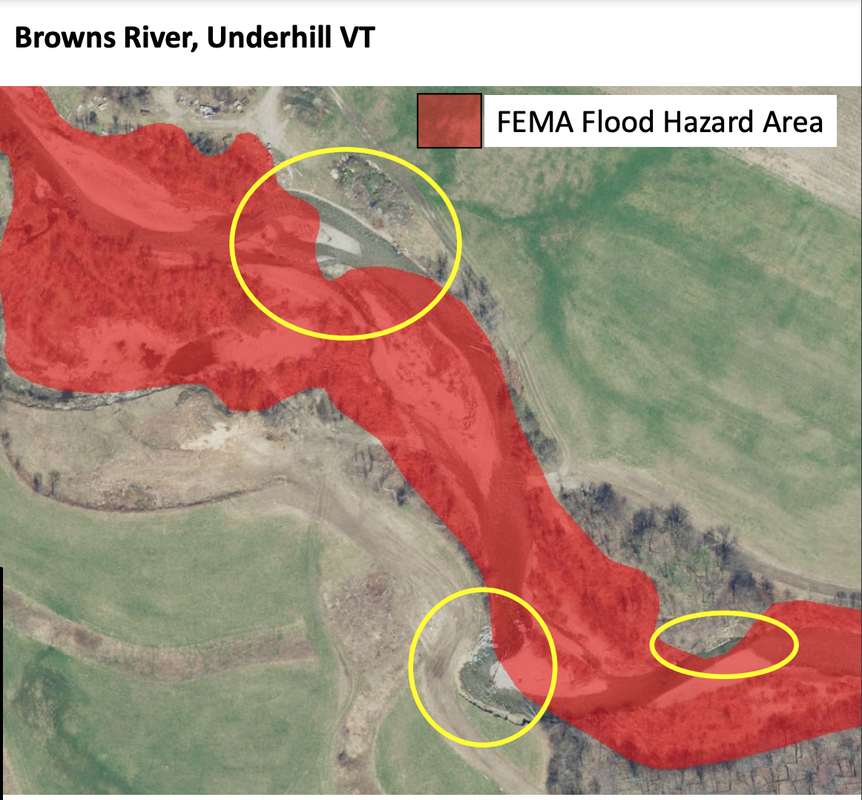

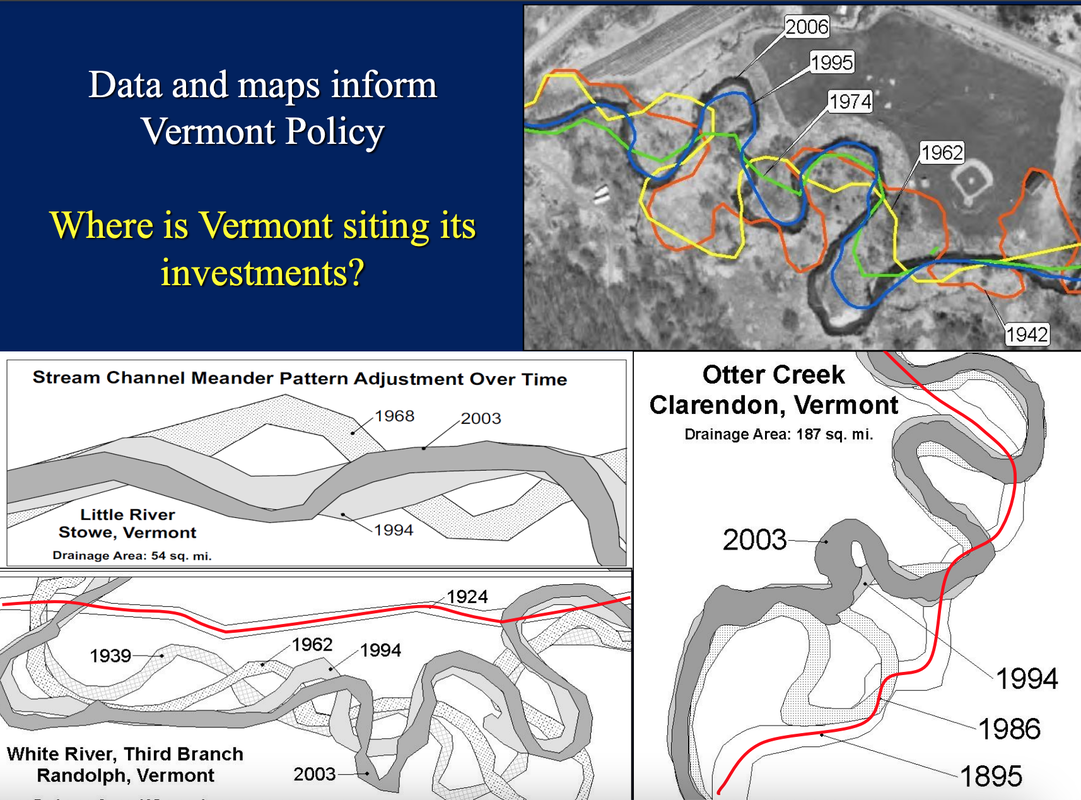

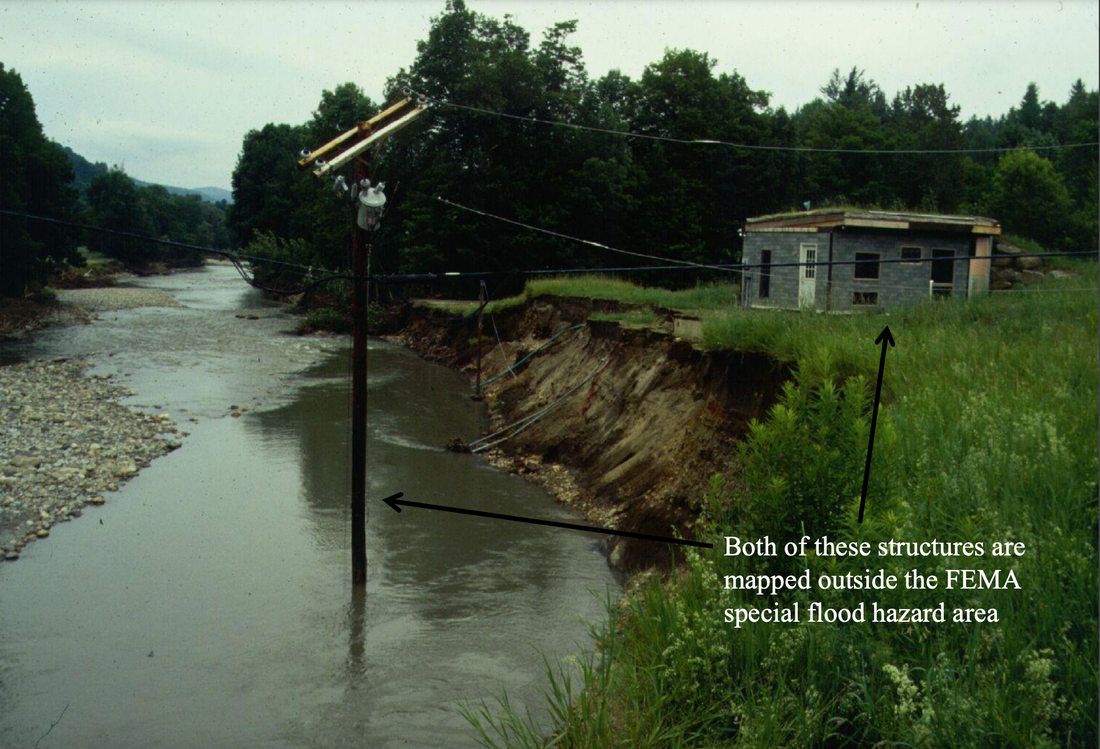

Now, to be fair, we've got a long way to go before any of this makes it to the floor for a vote, but I wanted you to have at least the basics of the kind of shifts in Act 250 that may be coming. There's reason to be hopeful about land use planning in Vermont, and I'm looking forward to working further on these historic Act 250 reforms. We had lots of great testimony again this week, and while we're starting to get into some policy conversations, Natural Resources and Energy is still feeling like a science class (and I'm loving it - feeling right at home!) So again, I want to share some images with you that I found compelling. All of these images are screen shots from the presentations this week either by Mike Kline, Rebecca Pfeiffer, or Rob Evans. These folks helped me understand how to look at FEMA flood maps, helped me have a better understanding of the difference between a flood plain and a river corridor, and helped me understand how what we saw during the summer, was a part of the natural cycle for rivers that have been altered. It all starts with the stages of river channel evolution, as seen in the image below. The "incision" stage is when humans have messed with the river, either by armoring, straightening, dredging, berming, or removing wood, etc. It's just a matter of time before those human interventions ultimately cause the river to widen and re-stabilize. Currently 73.5% of Vermont's rivers are "moderately to severely incised". It turns out that the last time FEMA came through Vermont to update their flood maps was in the 1970s, at the height of Vermont's river incision. So when FEMA ran their algorithm that added some additional volume of water to river channels, because of the incisions, the "flood plain" perfectly overlapped the river channel itself in many places. This is what we're seeing in the image below, where the red 100 year flood plain shares much of the same boundaries as the river channel, implying that those surrounding fields are somehow safe for construction. And of course those static maps from the 1970s are not super helpful when the river itself is moving around the landscape. Check out the image below from Underhill where the river channel has already moved so much that the channel is outside of the flood hazard area (circled in yellow). How much do rivers change their shape on the landscape? Quite a bit. We saw some great examples of this, but my favorite is from the Third Branch of the White River (bottom left in the image below), where you can see that we straightened the river in 1924, but the river was just not having that and continued to wiggle its way across the landscape. It's important to note that those FEMA maps are all about the inundation hazard area. (Another way of saying a 100 year flood area is an area with 1% annual chance of flooding. The 500 year flood area has a 0.2% annual chance of flooding.) Inundation is just when the water rises, like we saw in downtown Montpelier. So these maps do not include the area at risk from erosion risk, when the river decides its time to carve a new path or re-stabilize its banks. This was the kind of damage we saw in Cabot (and many other places) in July and in the image below. The erosion hazard area is what is supposed to be captured in the "River Corridor" maps. So when you hear "FEMA flood plain" think inundation risk (waters rise), and when you hear "River Corridor" think about those wiggly lines all over the landscape and erosion risk. That's what the white-ish area is around the red flood plain in the first map. A couple points of good news:

I think we can all agree that while we must build more housing, it should NOT be in these high risk areas. I received the Vermont Conservation Voters Rising Start Award!In other news, I received the Vermont Conservation Voters Rising Star award for the Senate! (yay!) A physical award is still in the works, but they gave me a bar of chocolate as a placeholder until the real award arrives. The picture below is from the award ceremony held at Hugo's Bar and Grill. Since I won this award, I was interviewed on the Vermont Conservation Voter's Climate Dispatch podcast, which you can listen to here.

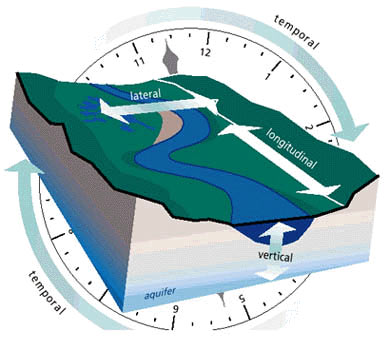

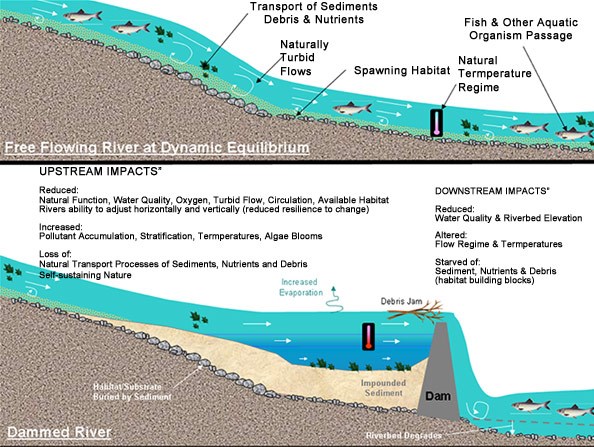

Coming back into the State House this week, the biggest priority on everyone's mind was flood recovery. We heard testimony in both Natural Resources & Energy and in Government Operations on it, and I wanted to pass along some of the most interesting images from testimony this week. Beyond the immediate needs of making those devastated by the floods whole, I'm very tuned into how are we going to prevent this kind of flooding from happening again in the future. We know climate change is here, but there are ways that we can improve our water management systems so that the effects of increased precipitation are reduced. I especially want to highlight the testimony we heard from Karina Dailey, a restoration ecologist with VNRC. You can see her slide deck here. I've pulled a couple of the images from her presentation from elsewhere on the web and included them below because they were (at least for me) some new learning that I found fascinating. And they say that the best way to learn something is to teach it, so I'm going to attempt to reiterate what I learned here. Karina's mantra was "INTACT FRESH WATER SYSTEMS BUILD CLIMATE RESILIENCE". How do we keep fresh water systems (like rivers) intact? To answer this, we have to consider the ways in which a river can change: laterally (shifting side-to-side), longitudinally (flowing down hill), vertically (connecting to ground water or aquifers), and temporally (shifting over time). If a river gets disconnected in any of these dimensions, that means bad news for ecosystems and for humans. For example, when large rain events occur, rivers need to be able to spread out their excess water into their flood plains (lateral movement), but if rivers are armored (walled or lined with granite blocks) then those flood plains are not accessible. Solution #1: Connect rivers back to their flood plains The second idea is re-connecting rivers vertically. How are rivers not intact now? Dams. Dams can raise the temperature of the water behind them (bad for ecosystems). They build up sediment behind them, which literally raises the water level behind them. Apparently they can also increase the water level in high rain events below them as well, though, I'm less clear as to why that occurs. Solution #2: Remove derelict dams Both of these solutions are baked into the language of

We heard during testimony that Vermont has lost 35% of its wetlands since European settlement, and as my colleague Sen. White observed, during this new era of climate change, we probably need more wetlands than we had then just to deal with the new, high-precipitation weather we're likely to experience with climate change. So one of the provisions in this bill aims to recover than we had. I hope you found this as interesting and informative as I found it! One other highlight from this week: I had the honor of speaking at the Rally for Flood Recovery on Wednesday, where I told the story about how a project in Northfield, which connected a river to its floodplain, lowered the water in the July flooding by 6 inches. To quote Michelle Braun of Friends of the Winooski, "6 inches may not seem like a lot, but when that's in your living room, it makes a big difference." Psyched for Week 2! Here we go! |

Details

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed